Pray. Read. Write.

This three-part creative process is one of the most enduring patterns of work in my life.

I have been praying and reading and writing and creating as long as I can remember. They are the forms of human searching and striving that animate my life. And they are the kind of meaning making that make the most sense to me. So I was a good student. But not just because I was a teacher pleaser. (I was that.) But because reading and writing gave me meaning. It became a mode of being seen in a world that otherwise lacked the rich connections I longed for and only found in books.

I won a school-wide essay contest about America’s Bicentennial in Mrs. Half and Mrs. Warner’s fourth grade class. And I guess that pretty much sealed the deal.

So grade school, high school, and college were filled with writing tasks and stacks of reading, memorizing scripture, and teaching younger children. And each task required writing and creating. Through excelling in the churchy and schoolish tasks of prayer, reading, and writing, I saw the world in a new way, and I felt seen by my teachers and professors. They all seemed to assume I would keep going.

And I did.

Praying in so many words

With college behind me, magna cum laude, I spent the next 10 years walking the path of seminary-search-congregational-call. Prayer in this season involved mostly words. I tried meditation and silence on many occasions. I even tried each morning for several weeks once while in seminary. But it didn’t stick. I was a genuine failure at meditation.

In other words, it was not my calling.

As I have said before, praying in silence (and praying in any fashion) is a vocation. It needs a deeper sense of purpose and calling for it to stick. This idea is not original with me. Yet I have found it experientially true. So I encourage people to try different forms of prayer and meditation, spiritual practices in great variety. And I warn them… it might only stick if it comes with a calling, and if there’s a community to support it.

In the years of seminary and then my first call to congregational ministry, I was on the cataphatic way. I was reaching out to God with words. So many words. Reading them and comprehending them. Diving into deep conversations with people who spoke the language I needed. And I was learning to craft more public words in prayers, sermons, and in my first published writing.

I only really learned to pray with the practices of meditation and the language of silence at the end of my time in congregational ministry. I was desperate. And the meanings and purpose in my life had worn thin.

I simply ran out of words.

That’s when I learned to pray in God’s language.

Silence.

Perhaps you would like to give it a try?

Praying in silence

The years of doctoral study at Vanderbilt and my first five years of academic work were grounded in a daily practice of centering prayer. The 20-minute morning meditation opened my mind, released me from daunting emotions, and it held every aspect of my life. The prayer of silence as a holding space worked because every small and enormous thing that came into the prayer was also free to go.

I was on the apophatic way.

What Martin Laird calls entering the silent land.

Thirteen years of daily practice changed me in many ways. Opening up space in my heart and mind, softening blocked pathways, giving me courage to face new challenges. Allowing my thinking to shift into habits of pastoral theology. Even in pregnancy, loss, and becoming a mother, daily meditation practice grounded me.

Praying in silence and word

Then nearly 10 years ago, when my first full-time academic job ended, I entered a time of major transitions. And I lost some important things, including my daily practice of prayer. I grieved the loss of that practice. So hard. And there didn’t seem to be anything I could do about it. I could try. I could sit. But the calling had changed.

The prayer had shifted more fully into my body and mind, residing with me always.

I was on a logophatic path.

Yet it took me a long time to truly see it. I had been teaching about logophasis for several years by then. The first class I taught at Luther Seminary, following Mary Moschella’s advice to teach what I wanted first and not wait, was “Prayer and Pastoral Care.”

Although I’ve taught it only four times in three schools, it remains my favorite course. In the class I teach the concept of logophasis. Coined by Martin Laird, and introduced to me by Maggie Ross, the concept brings together cataphatic and apophatic ways a prayer.

Logophasis

In his book on Gregory of Nyssa, Martin Laird introduces the term “logophasis” to express the full unity and paradox of word and silence. He suggests that the pathways of cataphatic and apophatic prayer can be understood more fully as co-inhering in a divine and simultaneous union of prayers, flowing into and out of each other.

Word and silence are inseparable. They coinhere as Laird says. There is silence built into every word, literally between every sound. We could not understand sounds without the silences interwoven in them, buried deep in the syllables, and between every word. (In the alternative, language would be one continuous incomprehensible sound.) Language must breathe, and so must prayer.

And we can only arrive at a more extended silence (like meditation) through words and language that lead us there. Certainly, art and music and other aesthetics can also lead us into profound and holy silence, the wonder and awe of beholding. And yet we would not know what art or music or aesthetics were without words to convey them, to teach us and lead us. One simply cannot do without the other. And yet finding a way to speak about prayer and to experience sacred presence is richer when we understand how word in silence relate. Coinhere. Unite in logophatic process.

This idea transfigured my own imagination.

Eventually it transfigured my body and mind.

I didn’t actually lose my meditation practice so much as it became lodged deeply in my thought patterns, I work habits, my way of being in the world.

A New Way: Praying. Reading. Writing

For sure since 2013, I have been on what looks mostly like a cataphatic path, using words for prayer, reading, and writing. I wrangle words for teaching and blogging and publishing and preaching. I have written books and articles, both academic and popular. Last week I spoke about the way public theology and practice is essential for my work. Because I want good ideas to get into the public thanking and discussion. And also because I’ve had few other choices with an erratic jungle-gym career path.

And I am strangely both an extrovert, profoundly energized by my conversations in and with the presence of other people. And at the same time, I am deeply in need of silence and stillness and uninterruption.

What is hidden to others mostly, is how the years of meditation practice changed mine thought patterns and ways of taking in the processing what I read and write. That hidden gift of prayer, meditation with any breath, seeing and being seen by the sacred in everything… these animate my work, my relationships, my life. This reality is largely beyond saying. Yet sometimes it is important to try.

This summer

This summer I am making some deliberate commitments to praying and reading and writing in new ways.

I’m am testing the waters to ask: am I again called to a daily renewed practice of 20 minutes of sitting in centering prayer? In particular, I am discerning that call because of the tremendous ambiguous loss and pervasive grief of the last three years. And I am seeking a shelter from the relentless barrage of sound and fury from my cell phone, my computer screen, newspapers, scholarly articles, preachers and pundits, among whom I am one.

To say anything of substance in these days, anything that cannot simply be generated by Chat GPT or found in a Google search, requires a different quality of silence.

When I teach “Prayer and Pastoral Care,” I invite students to begin noticing the quality of silence in a song, a sermon, spoken prayer, a place, or a person. We all carry within us deep wells of silence because silence is what holds everything.

Yet it is easy in this world of searching and striving to miss the fact of the deep language of God’s silence and profound presence that upholds, supports, and animates the universe. The seeming emptiness in every cell and atom, and between planets and galaxies in outer space and in the atmosphere that holds us on the planet and fills our lungs with life, is in reality an abundance of presence.

This life-giving presence restores my soul.

This summer I’m continuing to listen and to explore the quality of silence in my praying and reading and writing.

How will you notice the quality of silence in your life? What is your calling in this season?

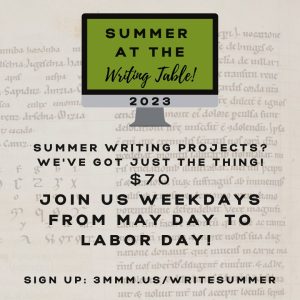

If your summer calling and plans include writing, I hope you will consider joining me at the Writing Table!

If your summer calling and plans include writing, I hope you will consider joining me at the Writing Table!

Join for the entire summer and come any weekday from May – August that suits you! Fridays at the Writing Table remain free. Sign up for #FreeWrite Fridays and get a weekly email with a link. Invite your writing friends. We always give a prompt to get you started on Fridays — if you need it!